Approximate Mapping of Nanopore Squiggle Data with Spatial Indexing

Nanopore data

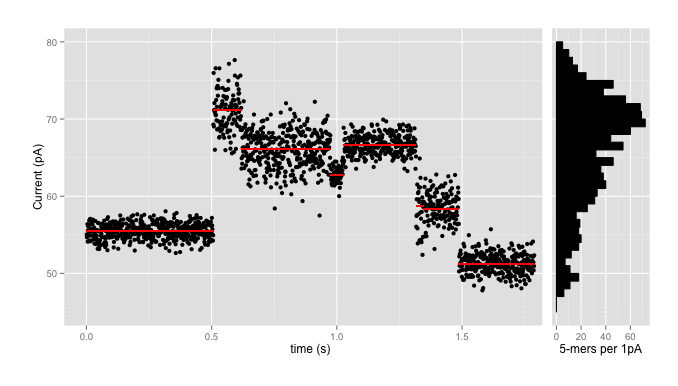

Here at the Simpsonlab we work with signal-level data from nanopore sequencers, particularly those from ONT like the MinION. Signal-level data looks something like this:

where the data comes in as a stream of events (the red lines) with means, standard deviations, and durations, with each black point being an individual signal reading. We use the signal-level data partly for accuracy - because converting each red line and dozens of black points into one of four letters invariably loses lots of information - and partly because those basecalls might not be available in, say, the field, where the portability of the nanopore sequencers really shines.

This data has to be interpreted in terms of a particular model of the interaction of the pore and the strand of DNA; such a pore model gives, amongst other things, an expected signal mean and standard deviation for currents through the pore when a given \(k\)mer is in the pore (for the MinION devices, pore models typically use \(k\)=5 or 6). So a pore model might be, for \(k\)=5, a table with 1024 entries that looks something like this:

| kmer | mean | std dev |

|---|---|---|

| AAAAA | 70.24 | ± 0.95 pA |

| AAAAC | 66.13 | ± 0.75 pA |

| AAAAG | 70.23 | ± 0.76 pA |

| AAAAT | 69.25 | ± 0.68 pA |

| … | … | … |

and using such a pore model it’s fairly straightforward to go from a sequence to an expected set of signal levels from the sequencer: so, say, for the 10-base sequence AAAAACGTCC and the above 5-mer pore model we’d expect 6 events (10-5+1) that look like:

| event | kmer | mean | range (1\(\sigma\)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| e1 | AAAAA | 70.2 pA | 69.3 - 71.2 pA |

| e2 | AAAAC | 66.1 pA | 65.4 - 66.9 pA |

| e3 | AAACG | 62.8 pA | 62.0 - 63.6 pA |

| e4 | AACGT | 67.6 pA | 66.3 - 68.9 pA |

| e5 | ACGTC | 56.6 pA | 54.5 - 58.7 pA |

| e6 | CGTCC | 49.9 pA | 49.1 - 50.7 pA |

Using those models, plus HMMs and a tonne of math, Jared’s nanopolish tool has had enormous success improving the quality of nanopore reads and assemblies of nanopore data. As one can see from the ‘range’ column above, and from the histogram on the side of the first plot, which shows the numbers of kmers which fall into 1pA bins in the pore model, this isn’t necessarily particularly easy. There are over 70 kmers which are expected to have means in the range 69.5pA - 70.5pA; that plus the wide standard deviations means that there is enormous ambiguity going back from signal levels to sequence.

Mapping

This ambiguity introduces complication into another part of the bioinformatics pipeline - mapping. While several mappers (BWA MEM, LAST) work quite well with basecalled ONT data, and one mapper1 has been written specifically for basecalled ONT data, mapping signal-level data directly is a little tougher. It is one thing for a seed sequence in the read to occur in multiple locations in the reference index; it is another thing for a sequence of floating-point currents to plausibly represent one of hundreds of seed sequences.

On the other hand, a flurry of recent important papers and software2

3 4 5, the first of which are discussed in some informative

blog

posts,

have demonstrated the usefulness of approximate read mapping. In

our case, mapping to an approximate region of a reference would

allow exact but computationally expensive methods like nanopolish

eventalign to produce precise alignments, or simple assignment may

be all that is necessary for other applications.

So an output approximate mapping would be valuable, but the issues remains of how to disambiguate the signal level values.

Spatial Indexing

Importantly, while any individual event is very difficult to assign with precision, sequences of events are less ambiguous, as any given event is followed, with high probability, by one of only four other events. Thus, by examining tuples of events, one can greatly increase specificity.

And there are well-developed sets of techniques for looking up lists of \(d\) floating point values to look for candidate matches: spatial indexes, where each query or match is considered as a point in \(d\)-dimensional space, and the goal is to return either some number of nearest points (k-Nearest-Neighbours, or kNN queries), or all matches within some, typically euclidean, distance.

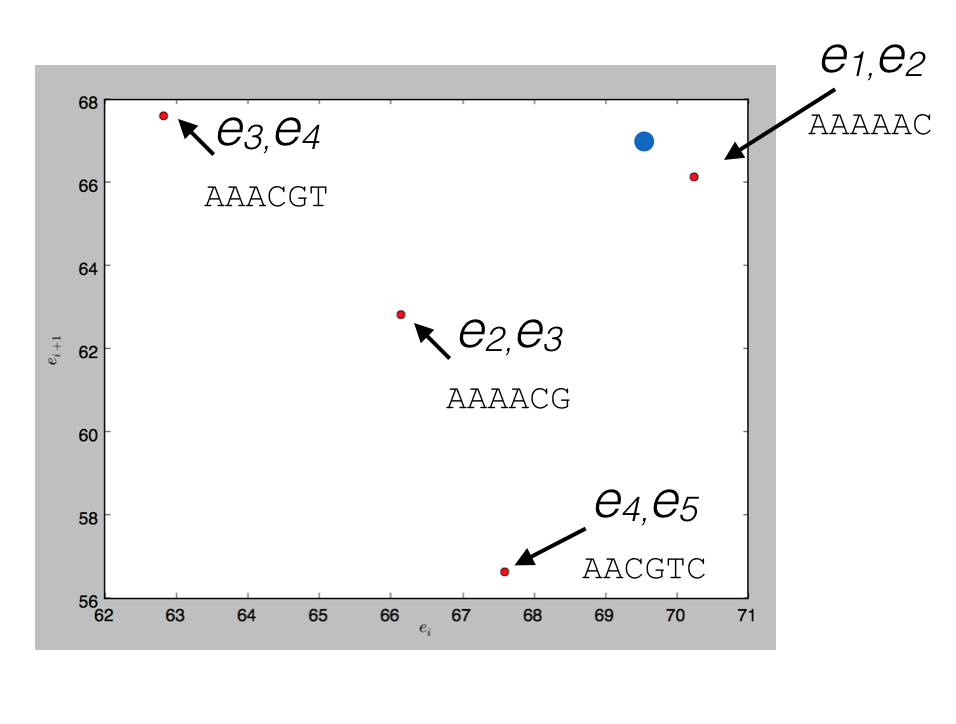

To see how this would work, consider indexing the sequence above, AAAAACGTCC, in a spatial index with \(d=2\). There are a total of 6 events, so we’d have 5 points (6-2+1), each points in 2-dimensional space; 4 are plotted below (the other falls out of the range of the plot)

and a query for \(d\) read events that could be matched by (69.5, 67), the blue point, would return the nearest match (70.2, 66.1) corresponding to the \(k+d-1\)-mer AAAAAC.

So to map event data, one can:

- Generate an index:

- Generate all overlapping tuples of \(d\) kmers from a reference

- Using a pore model, convert those into points in \(d\)-space

- Create a spatial index of those points,

- For every read:

- Take every overlapping set of \(d\) events

- Look it up in a spatial index

- Find a most likely starting point for the read in the reference, with a quality score.

Note that one has to explicitly index both the forward and reverse strands of the reference, since you don’t a priori know what the “reverse complement” of 65.5 pA is. One also has to generate multiple indices; for 2D ONT reads, there is a pore model for the template strand of a read, and typically two possible models to choose from for the complement strand of a read, so one needs three indexes in total to query.

What dimension to choose?

To test this approach, you have to choose a \(d\) to use. On the one hand, you would like to choose as large a dimension as you can; the larger \(k+d-1\) is, the more unique each seed is and the fewer places it will occur in any reference sequence.

On the other hand, two quite different constraints put a strong upper limit on the dimensions that will be useful:

- The curse of dimensionality - in high spatial dimensions, nearest-neighbour searching is extremely inefficient, because distance loses its discriminative power. (Most things are roughly equally far from each other in 100-dimensional space; there are a lot of routes you can take!) As a practical matter, for most spatial index implementations, for \(d > 15-20\) or so you might as well just do a linear search over all possible items;

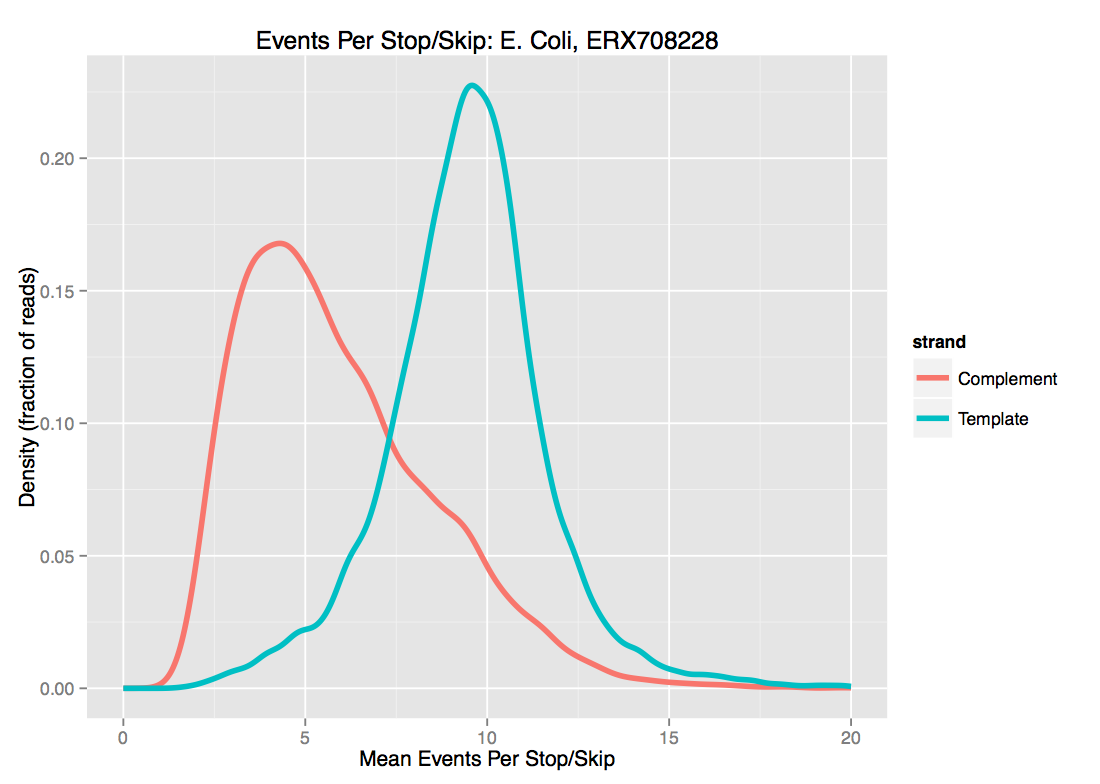

- Current approaches to segmentation mean that ONT data has very frequent ‘stops’ and ‘skips’ - that is, events are spuriously either inserted or deleted from the data. Exactly as with noisy basecalled sequences, this strongly limits the length of sequence that can be usefully used as seeds. As we see below for one set of E. coli data, there is probably not much point in using \(d \ge 10\) even for template-strand data, as the median “dmer” will have an insertion/deletion in it.

For these two reasons, we’ve been playing with \(d \approx 8\). I’ll note that while increasing \(d\) is the most obvious knob to turn to increase specificity of the match, higher \(k\) helps as well.

Normalizing the signal levels

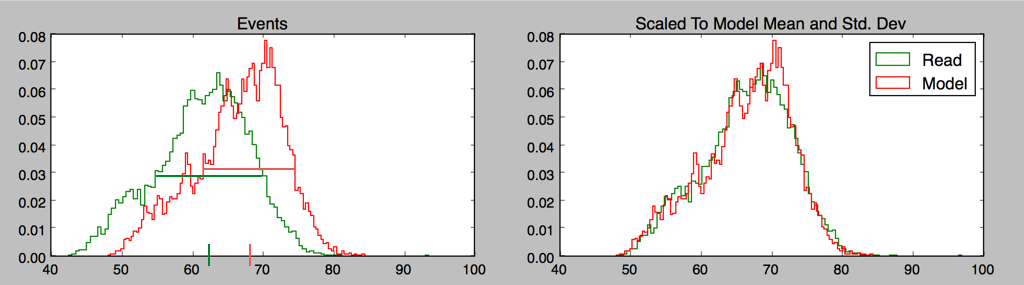

One issue we haven’t mentioned is that the raw nanopore data needs calibration to be compared to the model; there is an additive shift and drift over time, and a multiplicative scale that has to be taken into account.

A very simple “methods of moments” calculation works surprisingly well for long-enough reads, certainly well enough to start an iterative process; for any given model one is trying to fit a read to, rescaling the mean and standard deviation of read events to model events gives a good starting point for calibration, and drift is initially ignored.

Proof of concept

A simple proof of concept of using spatial indexing to approximately map squiggle data can be found on github. It’s written in python, and has scipy, h5py, and matplotlib as dependencies. Note that as implemented, it is absurdly memory-hungry, and definitely requires a numpy and scipy built against a good BLAS implementation.

As a spatial index, it uses a version of a k-d tree (scipy.spatial.cKDTree), which is a very versatile and widely used (and so well-optimized) spatial index widely used in machine learning methods amongst others; different structures may have advantages for this application.

Running the index-and-map.sh script generates an index for the provided ecoli.fa reference - about 1 minute per pore model - and then maps the 10 reads provided of both older 5mer and newer 6mer MAP data. Mapping each read takes about 6 seconds per read per pore model; this involves lots of python list manipulations so could fairly straightforwardly be made much faster.

Doing the simplest thing possible for mapping works surprisingly well. Using the same sort of approach as the first steps of the Sovic et al. method1, we just:

- Use the default k-d tree parameters (which almost certainly isn’t right, particularly the distance measure)

- Consider overlapping bins of starting positions on the reference, of size ~10,000 events, a typical read size

- For each \(d\)-point in the read,

- Take the closest match to each \(d\)-point (or all within some distance)

- For each match, add a score to the bin corresponding to the implied starting position of the read on the reference; a higher score for a closer match

- Report the best match starting point

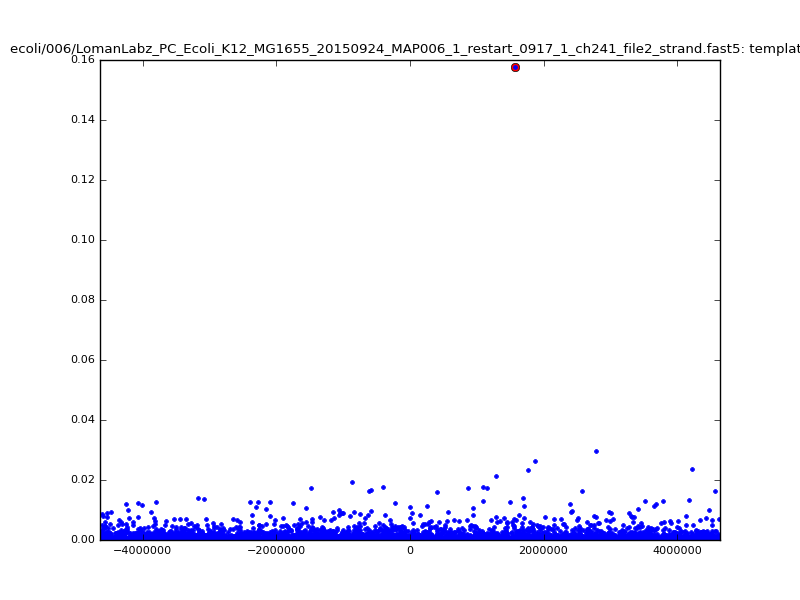

Let’s take a look at the initial output for the older SQK005 ecoli data and newer SQK006 data:

$ ./index-and-map.sh

5mer data:

Indexing : model models/5mer/template.model, dimension 8

python spatialindex.py --dimension 8 ecoli.fa models/5mer/template.model indices/ecoli-5mer-template

real 0m52.922s

user 0m49.756s

sys 0m1.196s

Mapping reads: starting with ecoli/005/LomanLabz_PC_Ecoli_K12_R7.3_2549_1_ch182_file148_strand.fast5

time python ./mapread.py --plot save --plotdir plots --closest --maxdist 3.5 \

--templateindex indices/ecoli-5mer-template.kdtidx

ecoli/005/LomanLabz_PC_Ecoli_K12_R7.3_2549_1_ch182_file148_strand.fast5 ... > template-005-.txt

real 1m9.776s

user 1m9.108s

sys 0m1.004s

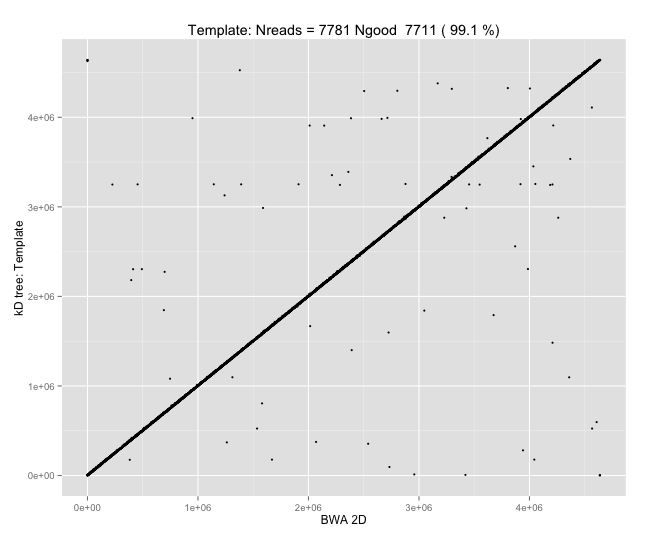

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch277_file143 819 3079177 3079996 17.164000

ch498_file171 1130 3793866 3794996 11.916000

ch222_file28 1765 2803231 2804996 11.152000

ch461_file9 1895 2195243 2193348 8.749000

ch182_file148 2559 2767555 2764996 17.120000

ch34_file53 4772 1128120 1123348 11.235000

ch401_file98 4981 2328329 2323348 6.160000

ch80_file64 5649 4369347 4374996 7.469000

ch395_file89 5828 2069168 2074996 9.517000

ch464_file15 7031 2195379 2188348 14.782000

Indexing : model models/5mer/complement.model, dimension 8

python spatialindex.py --dimension 8 ecoli.fa models/5mer/complement.model indices/ecoli-5mer-complement

real 0m52.124s

user 0m47.948s

sys 0m1.332s

Mapping reads: starting with ecoli/005/LomanLabz_PC_Ecoli_K12_R7.3_2549_1_ch182_file148_strand.fast5

time python ./mapread.py --plot save --plotdir plots --closest --maxdist 3.5 \

--templateindex indices/ecoli-5mer-template.kdtidx \

--complementindex indices/ecoli-5mer-complement.kdtidx \

ecoli/005/LomanLabz_PC_Ecoli_K12_R7.3_2549_1_ch182_file148_strand.fast5 ... \

> template-complement-005-.txt

real 1m47.590s

user 1m46.228s

sys 0m1.712s

Template+Complement Alignements

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch401_file98 19 2328329 2328348 7.516000

ch277_file143 819 3079177 3079996 17.164000

ch498_file171 1130 3793866 3794996 11.916000

ch222_file28 1765 2803231 2804996 11.152000

ch461_file9 1895 2195243 2193348 10.378000

ch182_file148 2559 2767555 2764996 17.120000

ch34_file53 4772 1128120 1123348 11.235000

ch80_file64 5649 4369347 4374996 7.469000

ch395_file89 5828 2069168 2074996 9.517000

ch464_file15 7031 2195379 2188348 14.782000

6mer data:

Indexing : model models/6mer/template.model, dimension 8

python spatialindex.py --dimension 8 ecoli.fa models/6mer/template.model indices/ecoli-6mer-template

real 1m4.028s

user 0m57.924s

sys 0m1.872s

Mapping reads: starting with ecoli/006/LomanLabz_PC_Ecoli_K12_MG1655_20150924_MAP006_1_5005_1_ch102_file146_strand.fast5

time python ./mapread.py --plot save --plotdir plots --closest --maxdist 3.5 \

--templateindex indices/ecoli-6mer-template.kdtidx \

ecoli/006/LomanLabz_PC_Ecoli_K12_MG1655_20150924_MAP006_1_5005_1_ch102_file146_strand.fast5 ... > template-006-.txt

real 1m46.643s

user 1m45.636s

sys 0m1.276s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch383_file65 844 89152 89996 20.490000

ch209_file0 1119 4564467 4563348 24.038000

ch485_file6 1739 400087 398348 23.698000

ch179_file92 3113 496461 493348 16.477000

ch102_file146 4965 1378313 1373348 25.003000

ch241_file2 5625 1578973 1573348 5.919000

ch339_file119 5710 829058 823348 22.348000

ch412_file79 5806 2194190 2199996 19.218000

ch228_file128 5933 3809063 3814996 17.926000

ch206_file36 11173 4373823 4384996 28.011000

Indexing : model models/6mer/complement_pop1.model, dimension 8

python spatialindex.py --dimension 8 ecoli.fa models/6mer/complement_pop1.model indices/ecoli-6mer-complement_pop1

python spatialindex.py --dimension 8 ecoli.fa models/6mer/complement_pop2.model indices/ecoli-6mer-complement_pop2

[..]

Mapping reads: starting with ecoli/006/LomanLabz_PC_Ecoli_K12_MG1655_20150924_MAP006_1_5005_1_ch102_file146_strand.fast5

time python ./mapread.py --plot save --plotdir plots --closest --maxdist 3.5 \

--templateindex indices/ecoli-6mer-template.kdtidx \

--complementindex indices/ecoli-6mer-complement_pop1.kdtidx,indices/ecoli-6mer-complement_pop2.kdtidx \

ecoli/006/LomanLabz_PC_Ecoli_K12_MG1655_20150924_MAP006_1_5005_1_ch102_file146_strand.fast5 ... > template-complement-006-.txt

real 3m55.773s

user 3m31.032s

sys 0m4.364s

Template+Complement Alignements

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch383_file65 844 89152 89996 20.490000

ch209_file0 1119 4564467 4563348 24.038000

ch485_file6 1739 400087 398348 23.698000

ch179_file92 3113 496461 493348 16.477000

ch102_file146 4965 1378313 1373348 25.003000

ch339_file119 5710 829058 823348 22.348000

ch412_file79 5806 2194190 2199996 19.218000

ch228_file128 5933 3809063 3814996 17.926000

ch241_file2 9375 1578973 1588348 11.626000

ch206_file36 11173 4373823 4384996 28.011000We see a couple of things here:

- Adding the complement strand does almost nothing for the accuracy, but requires substantially more memory and compute time, as multiple indices must be loaded and used up, and all candidate complement indices must be compared against each other. Because of this and the typically higher skip/stay rates for complement strands, we will use the template strand only for the rest of this post;

- Since we are simply assigning starting bins at this point, any assignments within the bin size are equally accurate; here, all of the reads were correctly assigned to the starting bin or the neighbouring one.

- The newer 6mer data gives slightly better results; part of this is likely because we are using the same \(d\), so a dmer for the k=6 data corresponds to seed longer by one

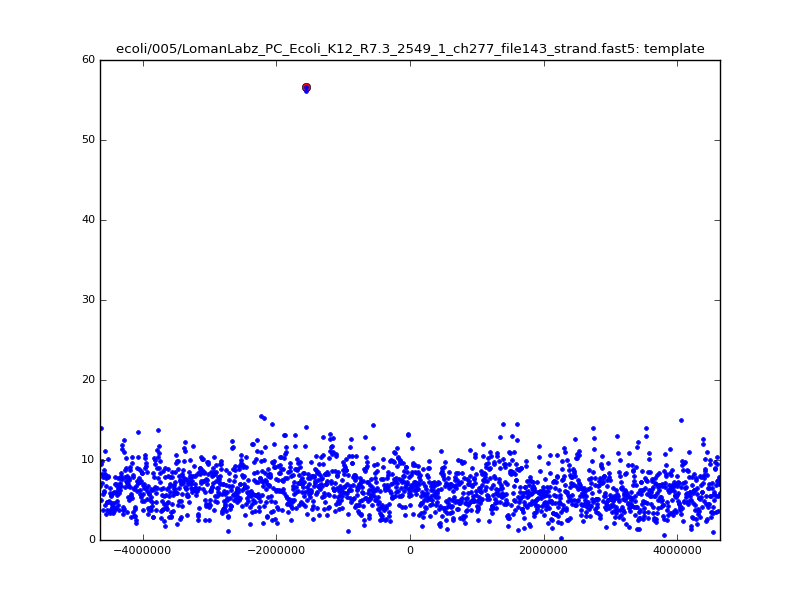

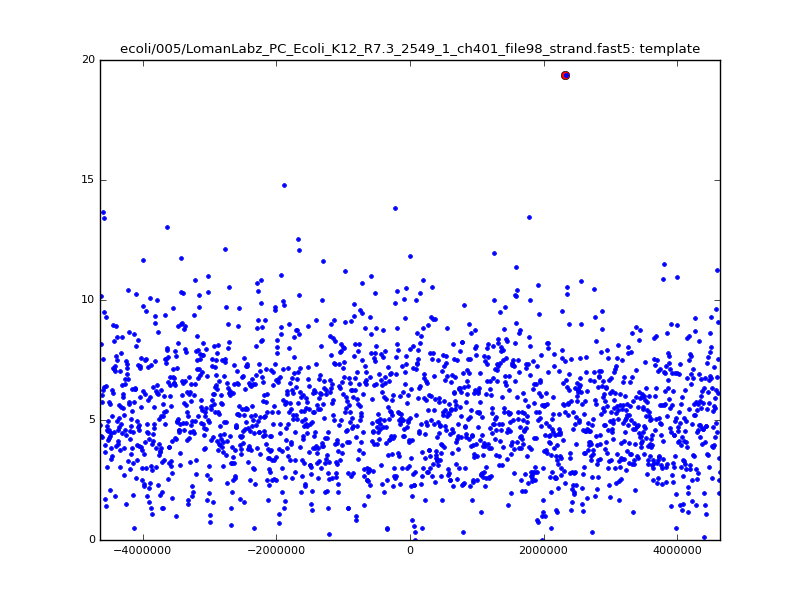

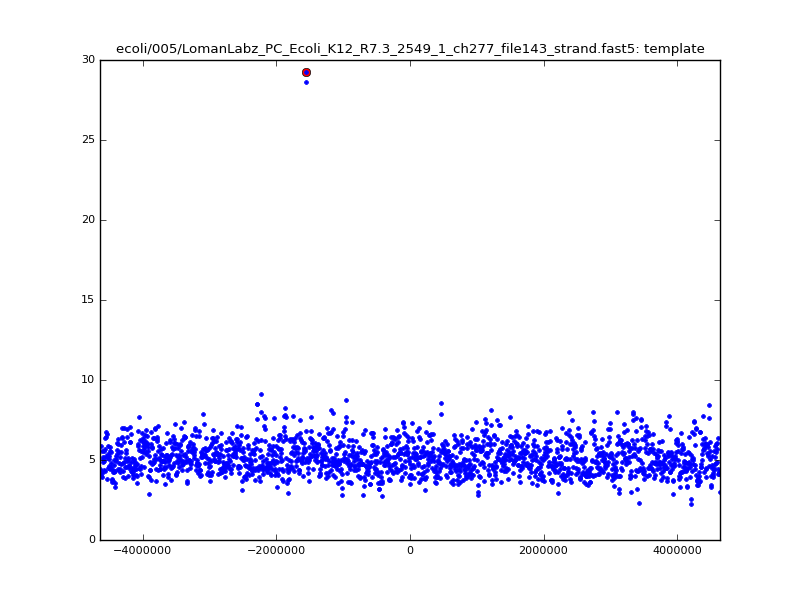

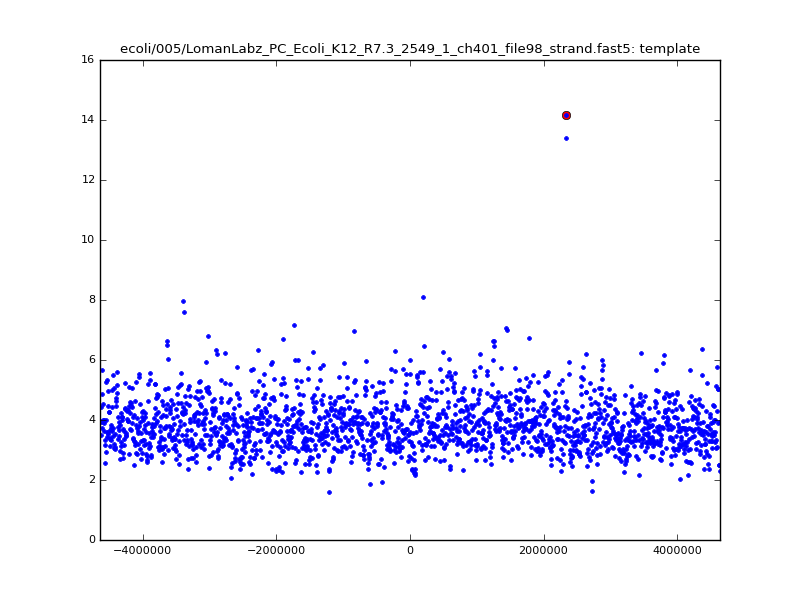

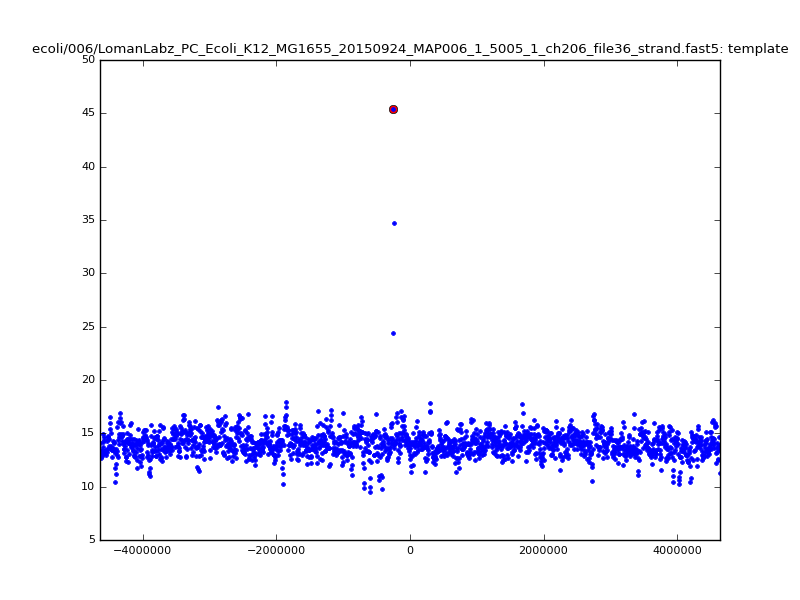

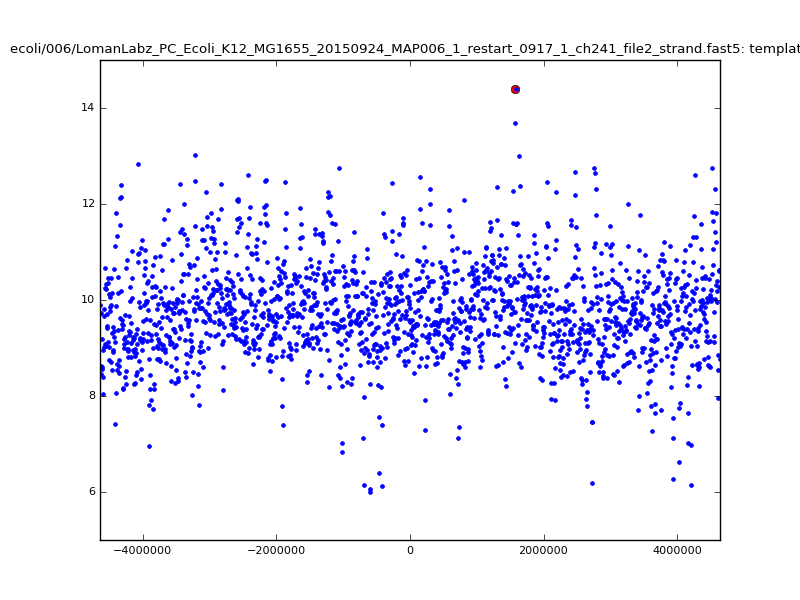

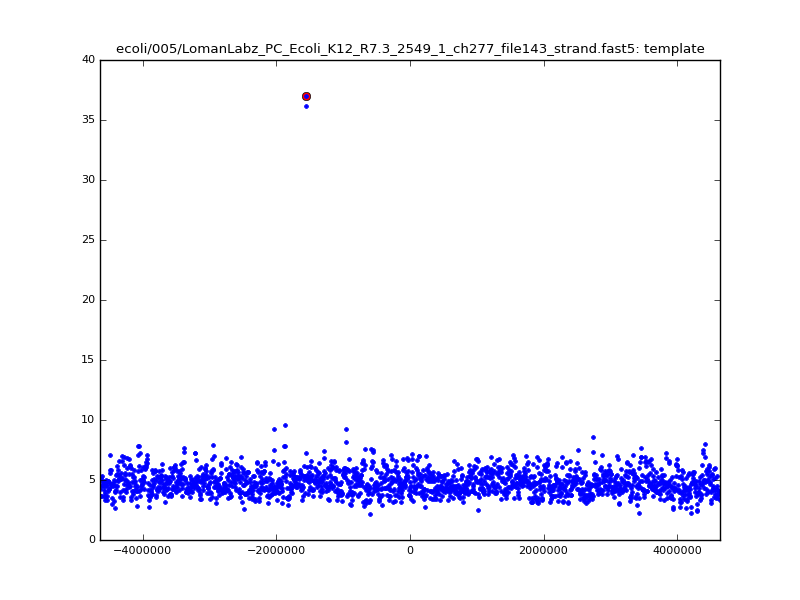

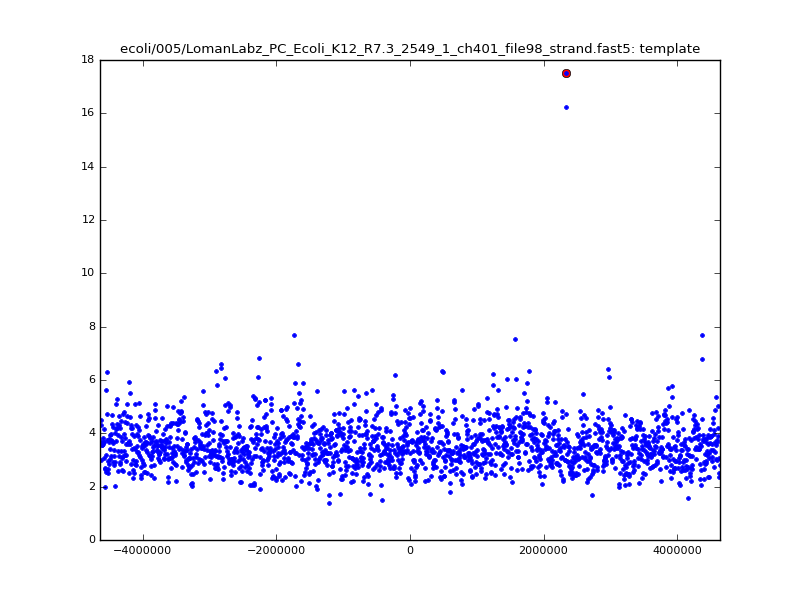

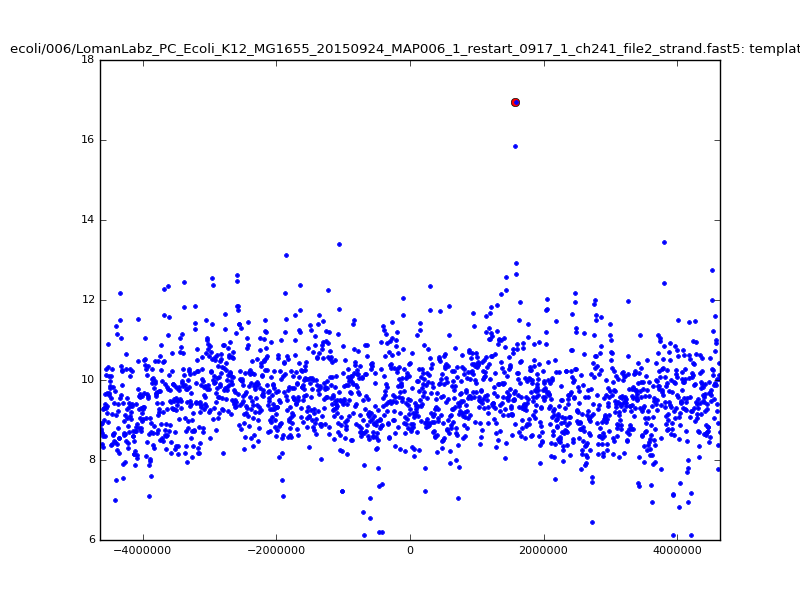

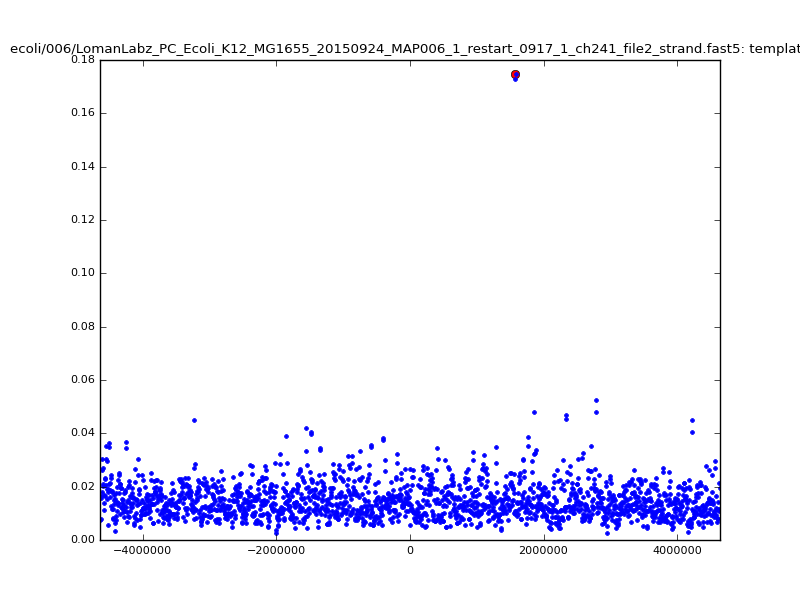

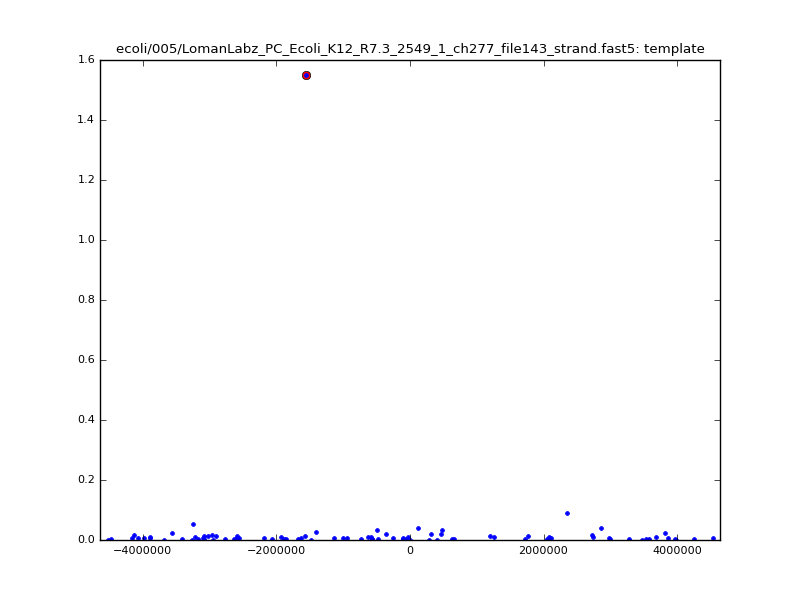

- The zscore here is a very crude measure of how much the assignment stands out over the background (but not necessarily how it compares to other candidate mappings); some of these very simple pseudo-mappings are relatively securely identified, and others less so. The sum-of-scores for the reads with the best and worst zscore results are plotted below; no prize for guessing which is which:

| 5mer |  |

|

| 6mer |  |

|

Because many levels are clustered near ~60-70pA, many dmers are quite close to each other, and choosing simply the closest \(d\)-point is unlikely to give a robust result. Examining all possible matches in the spatial index within some given radius reduces the noise somewhat, at a modest increase in compute time:

$ ./index-and-map.sh noclosest templateonly

5mer data:

[...]

real 3m15.145s

user 3m5.840s

sys 0m2.972s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch401_file98 19 2328329 2328348 11.359000

ch277_file143 819 3079177 3079996 19.103000

ch498_file171 1130 3793866 3794996 15.353000

ch222_file28 1765 2803231 2804996 17.583000

ch182_file148 2559 2767555 2764996 18.579000

ch34_file53 4772 1128120 1123348 16.615000

ch80_file64 5649 4369347 4374996 10.181000

ch395_file89 5828 2069168 2074996 13.145000

ch461_file9 6895 2195243 2188348 10.431000

ch464_file15 7031 2195379 2188348 18.042000

6mer data:

[...]

real 9m29.562s

user 9m9.536s

sys 0m16.600s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch383_file65 844 89152 89996 21.777000

ch485_file6 1739 400087 398348 24.384000

ch179_file92 3113 496461 493348 19.718000

ch102_file146 4965 1378313 1373348 24.218000

ch241_file2 5625 1578973 1573348 7.311000

ch339_file119 5710 829058 823348 26.045000

ch228_file128 5933 3809063 3814996 20.042000

ch209_file0 6119 4564467 4558348 23.703000

ch412_file79 10806 2194190 2204996 21.677000

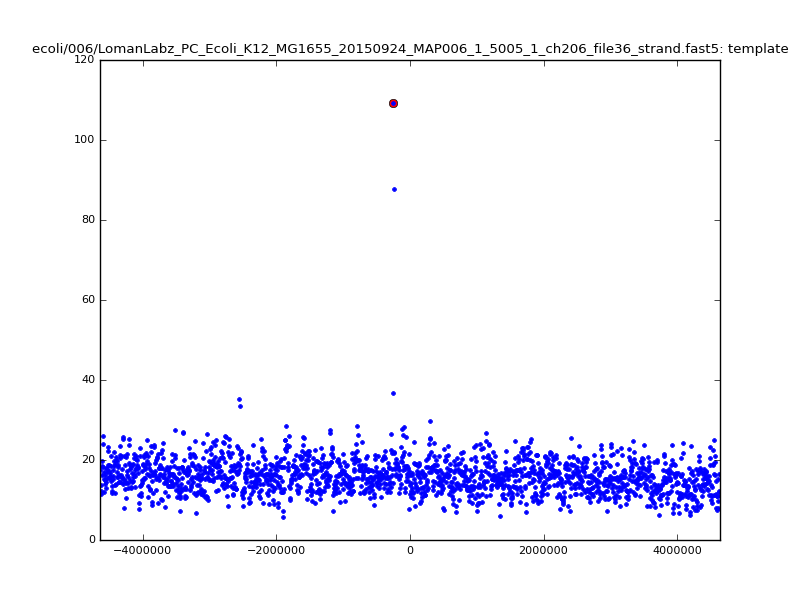

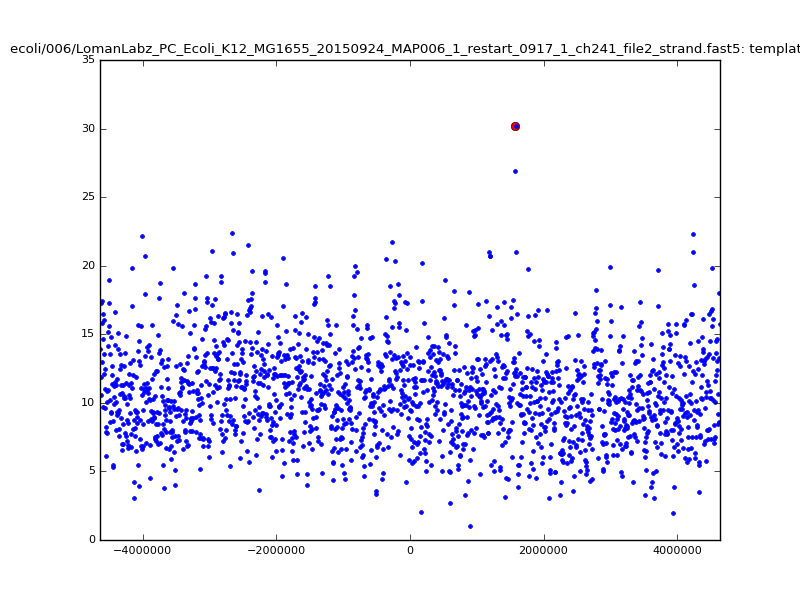

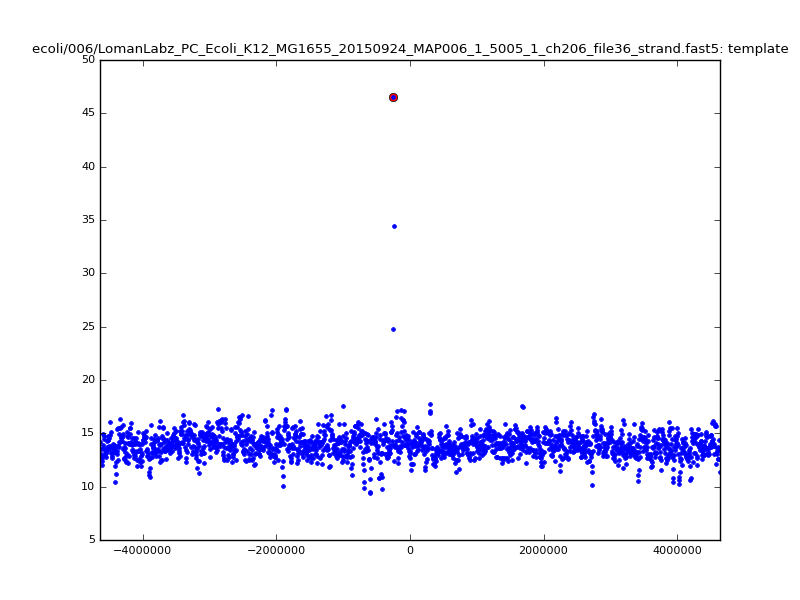

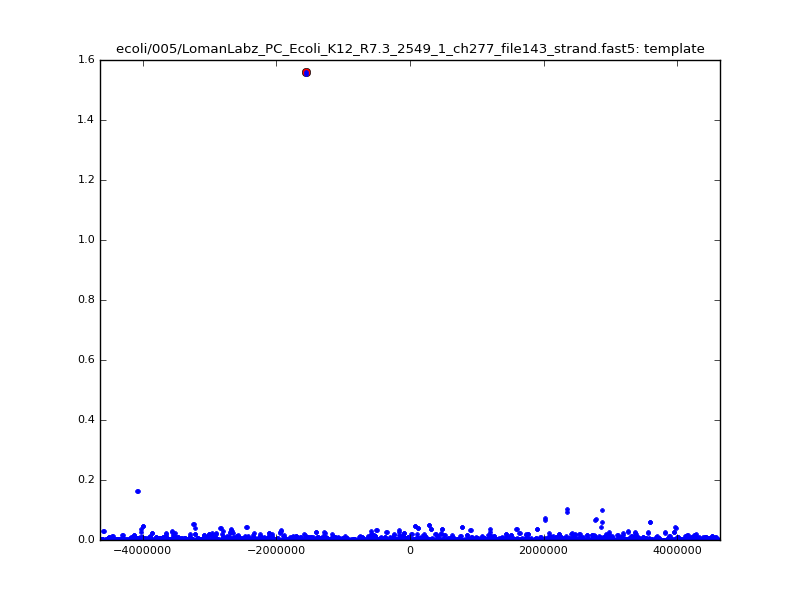

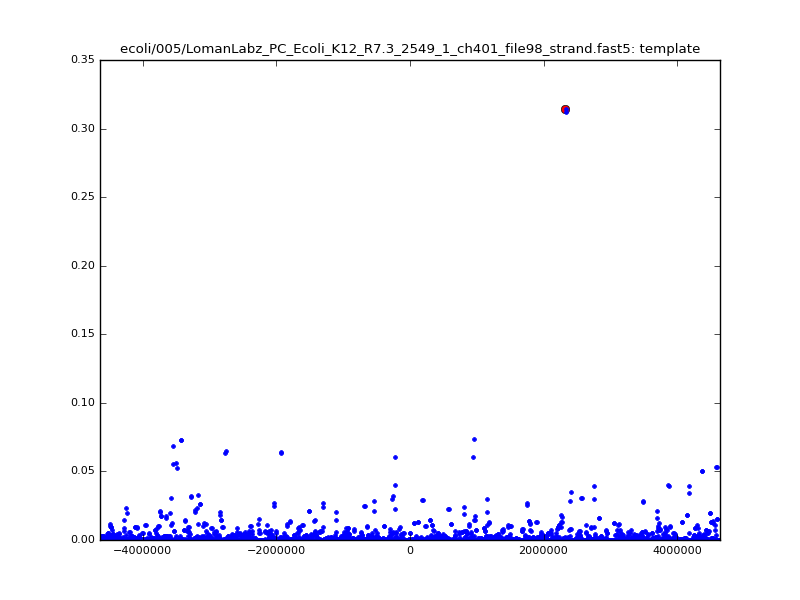

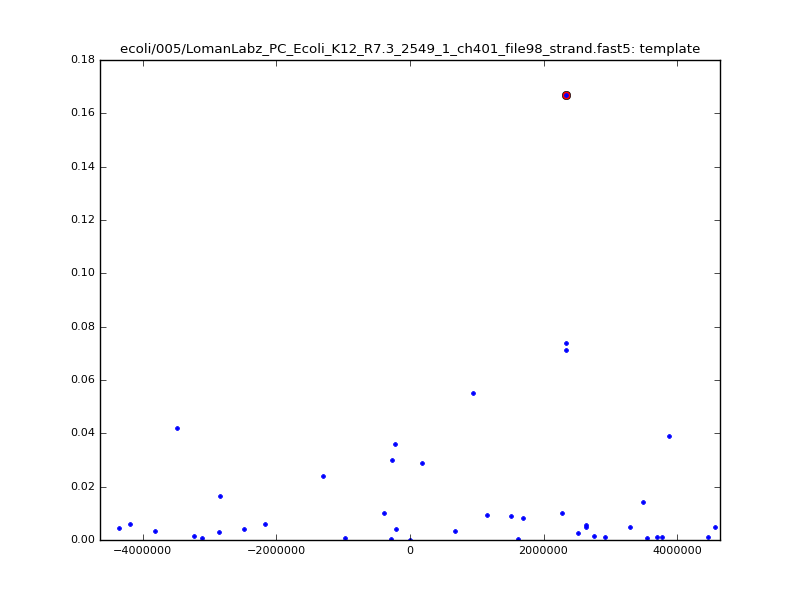

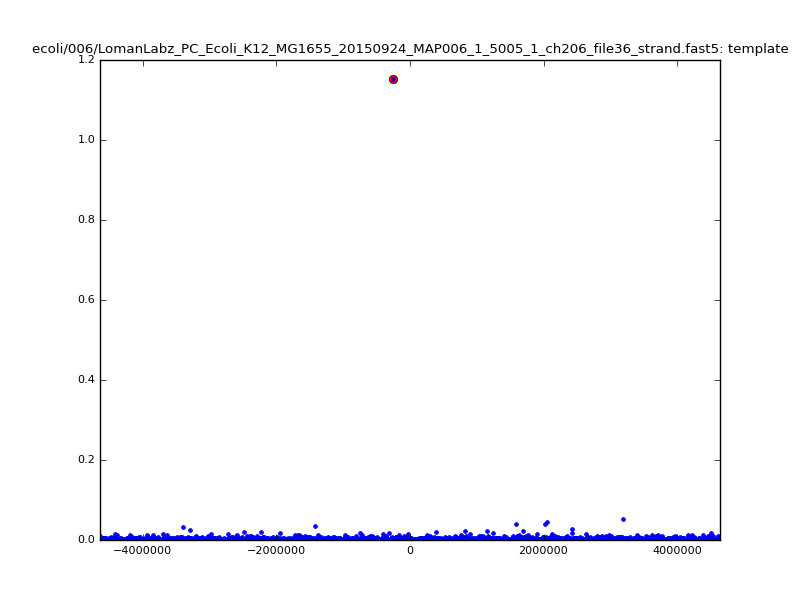

ch206_file36 11173 4373823 4384996 29.794000Note the increase in zscores; the same two reads are plotted:

| 5mer |  |

|

| 6mer |  |

|

With a few other tweaks - keeping track of the top 10 candidates, and for each re-testing by recalibrating given the inferred mapping and rescoring - we can get about 95%-99% accuracy in mapping.

Of course, while 95-99% (Q13-Q20) mapping accuracy on E. coli is a cute outcome from such a simple approach, it isn’t nearly enough; with \(d=8\) and \(k=5\), wer’e working with seeds of size 12, which would typically be unique in the E. coli reference, but certainly wouldn’t be in the human genome, or for metagenomic applications.

EM Rescaling

One limiting factor is the approximate nature of the rescaling so far that is being performed; for reads that have been basecalled, the inferred shift values above can be off by several picoamps from the Metrichor values, which clearly causes both false negatives and false positives in the index lookup. This can be addressed by doing a more careful rescaling step, using EM iterations:

- For the E-step, provisionally assign probabilities of read events corresponding to model levels, based on the Gaussian distributions described in the model and a simple transition matrix between events;

- For the M-step, perform a weighted least squares regression to re-scale the read levels.

This gives answers that are quite good when compared with Metrichor, at the cost of substantially more computational effort (much greater than the spatial index lookup!), particularly for long reads and larger (k) where the number of model levels is larger:

$ ./index-and-map.sh noclosest templateonly rescale

5mer data:

[...]

real 7m1.866s

user 6m56.708s

sys 0m29.236s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch401_file98 19 2328329 2328348 14.975000

ch277_file143 819 3079177 3079996 22.516000

ch498_file171 1130 3793866 3794996 20.894000

ch222_file28 1765 2803231 2804996 19.569000

ch182_file148 2559 2767555 2764996 20.443000

ch34_file53 4772 1128120 1123348 17.401000

ch395_file89 5828 2069168 2074996 13.510000

ch461_file9 6895 2195243 2188348 11.165000

ch464_file15 7031 2195379 2188348 19.315000

ch80_file64 10649 4369347 4379996 15.109000

6mer data:

[...]

real 33m11.324s

user 31m55.172s

sys 2m0.836s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch383_file65 844 89152 89996 23.732000

ch179_file92 3113 496461 493348 20.845000

ch102_file146 4965 1378313 1373348 24.997000

ch241_file2 5625 1578973 1573348 10.574000

ch339_file119 5710 829058 823348 26.816000

ch228_file128 5933 3809063 3814996 21.397000

ch209_file0 6119 4564467 4558348 24.546000

ch485_file6 6739 400087 393348 24.790000

ch412_file79 10806 2194190 2204996 25.477000

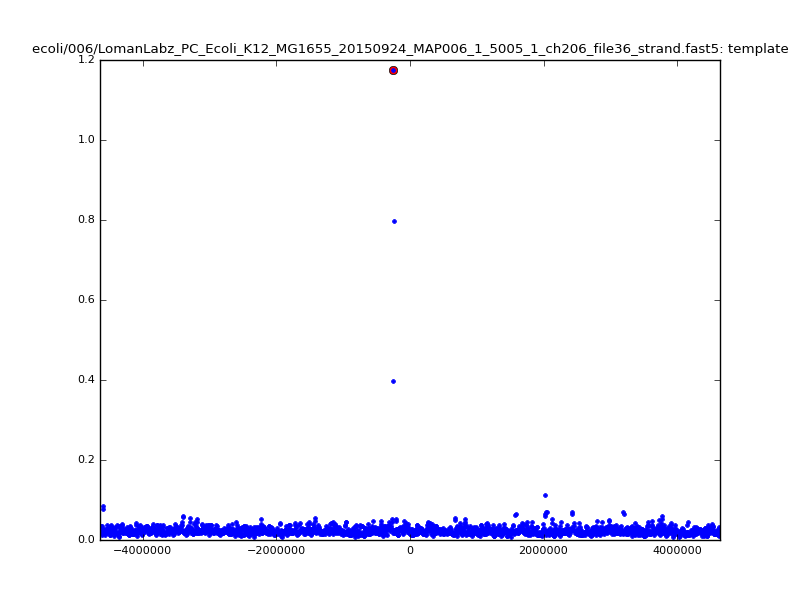

ch206_file36 11173 4373823 4384996 30.164000Note again the increase in zscores; replotting gives:

| 5mer |  |

|

| 6mer |  |

|

Extending the seeds

So far we have in no way taken into account any of the locality information in the spatial index lookup results; that is, that a long series of hits close together, in the same order on the read and on the reference, is much stronger evidence for a good mapping than a haphazard series of hits in random order that happen to fall within the same bin of starting points.

Keeping with the do-the-simplest-thing approach that has worked so far, we can try to extend these “seed” matches by stitching them together into longer seeds; here we build 15-mers out of sets of 4 neighbouring 12-mers, allowing one skip or stay somewhere within them, using as a score for the result the minimum of the constituent scores, and dropping all hits that cannot be so extended. This has quite modest additional cost, and works quite well:

$ ./index-and-map.sh noclosest templateonly rescale extend

5mer data:

[...]

real 7m20.914s

user 7m19.228s

sys 0m23.620s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch498_file171 1130 3793866 3794996 28.762000

ch222_file28 1765 2803231 2804996 27.434000

ch461_file9 1895 2195243 2193348 29.089000

ch182_file148 2559 2767555 2764996 29.538000

ch34_file53 4772 1128120 1123348 28.837000

ch401_file98 4981 2328329 2323348 23.840000

ch277_file143 5819 3079177 3084996 29.832000

ch395_file89 5828 2069168 2074996 23.705000

ch464_file15 7031 2195379 2188348 28.941000

ch80_file64 10649 4369347 4379996 26.926000

6mer data:

[...]

real 33m57.863s

user 32m58.236s

sys 1m42.548s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch241_file2 625 1578973 1578348 25.137000

ch485_file6 1739 400087 398348 30.297000

ch339_file119 5710 829058 823348 31.856000

ch383_file65 5844 89152 94996 30.163000

ch228_file128 5933 3809063 3814996 29.294000

ch209_file0 6119 4564467 4558348 30.169000

ch179_file92 8113 496461 488348 28.732000

ch102_file146 9965 1378313 1368348 30.107000

ch412_file79 10806 2194190 2204996 30.377000

ch206_file36 11173 4373823 4384996 33.896000| 5mer |  |

|

| 6mer |  |

|

Now that we seem to have much stronger and more specific results, we can investigate letting go of binning, and instead string these extended seeds into longest possible matches. Continuing to extend dmer-by-dmer is too challenging due to missing points (due to mis-calibration, too large noise in the dmer falling out of the maxdist window in the kdtree, or several skip/stays in a row), so following the ideas of graphmap1 and minimap5, we trace collinear seeds through the set of available seeds; rather than just taking longest increasing sequences in inferred start positions, however, we make a graph of seeds with edges connecting seeds that are monotonically increasing both in read location and reference location with ‘small enough’ jumps, and extract longest paths through this graph. The cost of this is smaller than the rescaling of the read.

Running this, the zscores now somewhat change meaning; only the extracted paths are scored, meaning that the scores are only amongst plausible mappings, not over all bins across the reference. Similarly, the differences in mapping locations are somewhat more meaningful - rather than being compared to bin centres, they are actually the differences between mapping locations.

We get:

5mer data:

[...]

real 6m54.776s

user 6m52.064s

sys 0m23.648s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch461_file9 10 2195243 2195253 7.105000

ch34_file53 343 1128120 1128463 12.449000

ch401_file98 363 2328329 2328692 5.320000

ch464_file15 2826 2195379 2192553 13.267000

ch498_file171 3192 3793866 3797058 7.688000

ch182_file148 5450 2767555 2773005 10.107000

ch222_file28 5681 2803231 2808912 8.166000

ch277_file143 6381 3079177 3085558 9.190000

ch395_file89 7191 2069168 2076359 7.685000

ch80_file64 15167 4369347 4384514 7.965000

6mer data:

[...]

real 43m37.651s

user 42m37.208s

sys 1m42.848s

Template Only Alignments

Read Difference BWA KDTree zscore

ch209_file0 14 4564467 4564453 31.724000

ch485_file6 14 400087 400073 24.063000

ch241_file2 203 1578973 1578770 26.676000

ch179_file92 723 496461 495738 39.626000

ch339_file119 774 829058 828284 45.636000

ch102_file146 1568 1378313 1376745 45.601000

ch383_file65 5890 89152 95042 27.902000

ch228_file128 8120 3809063 3817183 35.863000

ch412_file79 13833 2194190 2208023 48.444000

ch206_file36 15650 4373823 4389473 38.441000| 5mer |  |

|

| 6mer |  |

|

The simple python testbed implementation of these ideas linked to above is very slow, single-threaded, absurdly memory hungry, and its treatment of scores for the mappings does not currently make much sense. In the new year we will address these issues in a proper C++ implementation, where (for instance) we will not have multiple copies of large, reference-sized data structures.

References

-

Fast and sensitive mapping of error-prone nanopore sequencing reads with GraphMap (2015) by Sovic, Sikic, Wilm, et al. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Near-optimal RNA-Seq quantification (2015) by Bray, Pimentel, Melsted, and Pachter ↩

-

Salmon: Accurate, Versatile and Ultrafast Quantification from RNA-seq Data using Lightweight-Alignment (2015) by Patro, Duggal, and Kingsford ↩

-

Minimap and miniasm: fast mapping and denovo assembly for noisy long sequences, Heng Li ↩ ↩2